Please note: This school profile was written in 2019 as part of our "Climbing to Thriving" series highlighting bright spots in our public schools. The school data and other school information in this article are from 2019 and earlier.

Head Middle School

Building a Place to Belong

A case study in social, emotional, and academic development

Fifth grade Head Middle School teacher Mr. Harkins sits on the floor with two students surrounded by an array of 1-inch color tiles. The teacher asks the students to explain how they could use the tiles to portray a specific fraction using division. One child looks confused; the teacher asks the other child to provide some thoughts. As the fifth grader explains his thinking to his peer, both boys’ faces light up. The teacher compliments their efforts and moves on. Throughout the room, groups of two or three students are exploring fractions and other mathematical concepts using manipulatives like these tiles. Students are thoroughly engaged in their work, unaware that they are building not just their mathematical content, but social-emotional skills like effective communication, collaboration, problem-solving, and teamwork.

Social-emotional learning, or SEL, has been a buzz word in education for the last several years and is embedded in policies at all levels. All schools in MNPS incorporate some type of SEL skill-development for students, and Head Middle School is no exception. But we saw something at Head that felt unique – the intentional integration of social-emotional skill-development in all aspects of the school day – a deliberate recognition that school needs to help students develop skills not traditionally incorporated into the academic curriculum, like effective communication, collaboration, problem-solving, and conflict resolution. It is these skills that employers, parents, and families often point to as integral to success in life.

Baking SEL into Policy at All Levels

District

MNPS has been an official district partner with the leader in SEL skill-development, CASEL, since 2011, the same year the district formed an official SEL division

STATE

SEL is one of three pillars in the Tennessee Department of Education’s strategic plan

FEDERAL

Though the Every Student Succeeds Act doesn’t explicitly mention SEL, it provides opportunities for states to broaden their definitions of student success, and many have chosen to incorporate SEL as part of that new definition

Great teachers integrate social-emotional skills in academic content intuitively; they design their lessons with embedded opportunities for students to build relationships, practice empathy, reflect, and problem-solve. They emphasize student voice in lessons. They do less talking and more listening. They understand that relationship- and community-building in their classrooms are just as important as delivering content.

Head’s principal, Dr. Tonja Williams, recognizes and leverages her teachers who naturally embed social-emotional components while strategically implementing best practices across all classrooms. SEL is not left up to chance at Head – it is intentionally cultivated and harnessed schoolwide. “Three years ago, we were not where we are today with SEL practices,” said Head’s principal Dr. Tonja Williams. “We are on the ‘continuum’ for SEL, and are stronger because I was determined to see the work through and return to it year after year.” This work involves trainings, in-depth conversations, and daily reminders about what SEL should look like and feel like at Head, and is constantly modeled by how Dr. Williams and her leadership team engage with teachers and staff, to the point that it is embedded in the culture, mindsets, and behaviors at the school overall.

SEL is not left up to chance at Head – it is intentionally cultivated and harnessed schoolwide.

At Head, this is made possible by a clear vision that positions teachers as experts and leaders in their content and classrooms, and is supported by embedded structures and systems that clear the path for teachers to operationalize this vision. By creating an environment in which teachers are valued, supported, and taken care of, Dr. Williams believes they will be best positioned to do the same for students. She sees it as her job to ensure her teachers have the time, energy, and resources to focus exclusively on what they are delivering to students – how they are challenging and growing students academically, while helping them develop the personal agency and skills to think critically, make thoughtful decisions, and work well with others. “It’s what’s best for kids,” she said.

Learning through social, emotional, and academic skill-development

Research shows that an integrated approach to social, emotional, and academic development reinforces how we learn and take in information, and improves test scores in the process. As the Aspen Institute illustrates: “The promotion of social, emotional, and academic learning is not a shifting educational fad; it is the substance of education itself. It is not a distraction from the ‘real work’ of math and English instruction; it is how instruction can succeed.”1

Think about Mr. Harkins’ math lesson that combined the fifth grade standard of understanding fractions as division problems while explicitly embedding opportunities to practice teamwork, problem-solving, and communication. Or another example is Head’s new student-led Tiger Court that addresses mild student-disciplinary issues. Students act as judges, jury members, and bailiffs to hear cases, make rulings, and determine consequences for disciplinary infractions like disrespectful communication or disruptive lunchroom behavior. Students have an amplified voice for how their school operates, are developing their leadership and problem-solving skills, and also are learning about the judicial branch of government, democracy, and justice.

The students in this program remark that it has had a big impact on the overall culture of Head. The consequences are restorative – tied to the behavior infraction and aimed to solve problems long term and fix broken relationships – and students have been less likely to react negatively to consequences when they have been determined by their peers. One student on Tiger Court shares that students understand and respect the responsibility of the court to make judgments on and administer consequences to students – even for their friends. Students reflect that it isn’t personal; it’s how students are given the voice to be a fair decision-maker in their school. This student voice, which is particularly important for middle school students, is making an impact on Head’s culture and student experience. Between fall 2018 and fall 2019, Panorama data on whether students felt involved in helping to solve school problems increased by 13%.

Building culture to drive academic success

Dr. Williams, Head’s principal since 2012, understands that “SEL work is a paradigm shift for teachers. If you want teachers to believe in SEL, you have to believe in it as well.” And believe in it she does. Her vibrant and positive personality sets the tone daily for how the school will operate. In fact, 94% of Head’s teachers say leadership sets a positive tone for the culture of the school, according to fall 2019 Panorama data, compared to 68% on average for MNPS middle schools. What makes Head Middle special is not the novelty of their educational practices – many programs, ideals, and practices found at Head are in place at schools across our district, and around the country – but instead is the intentionality and cohesion in which they are cultivated.

What makes Head Middle special is not the novelty of their educational practices – many programs, ideals, and practices found at Head are in place at schools across our district, and around the country – but instead is the intentionality and cohesion in which they are cultivated.

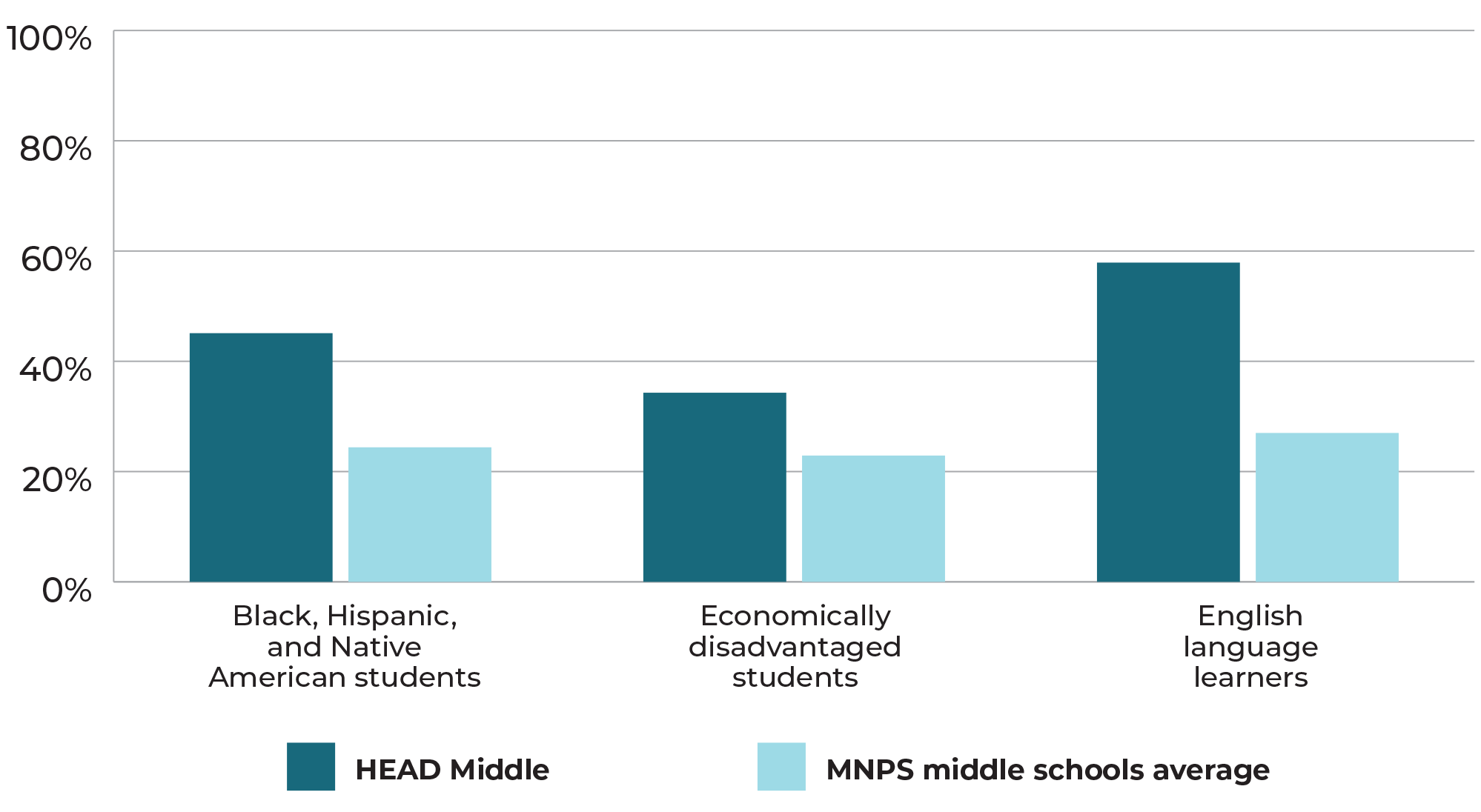

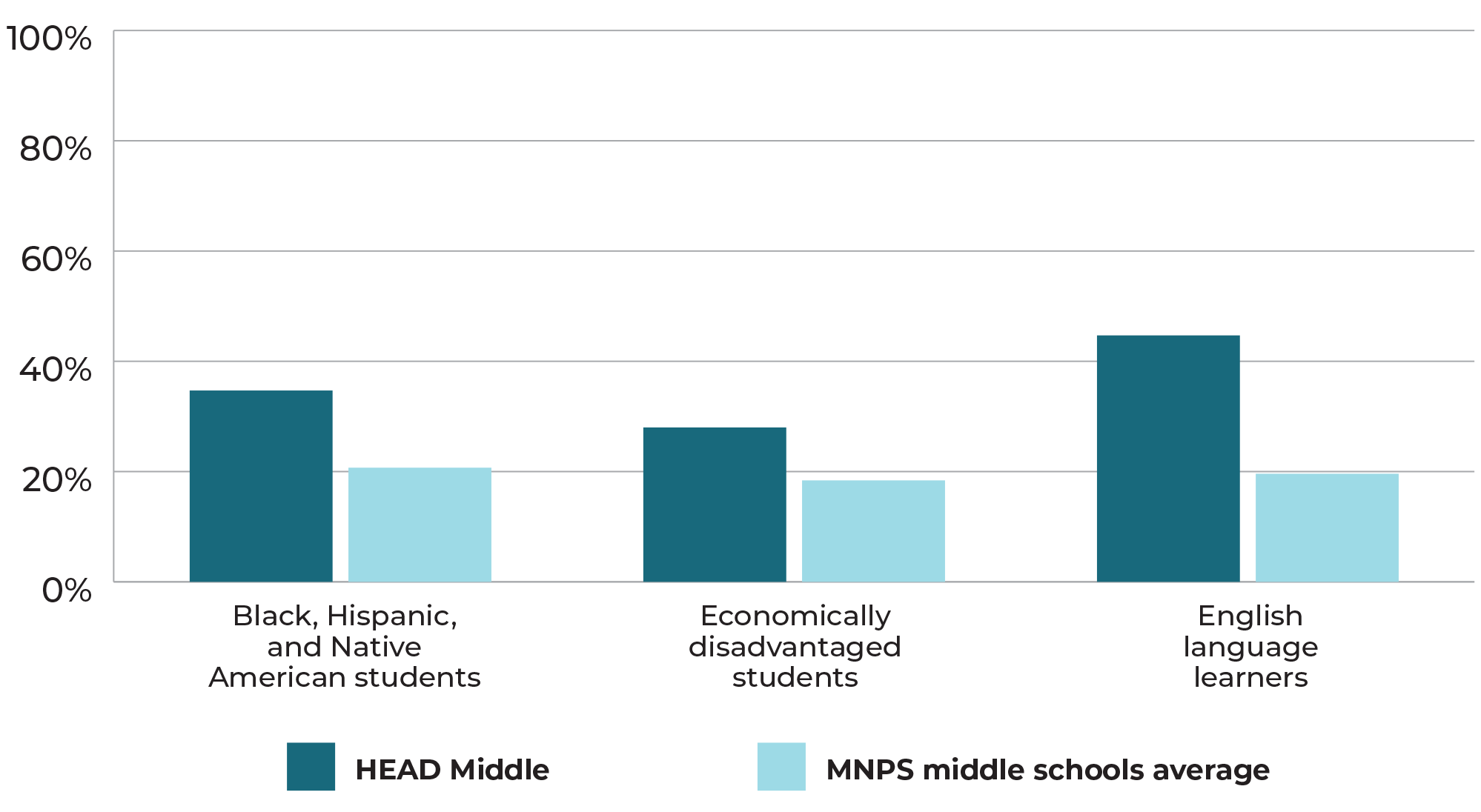

We know that something is working at Head because students and teachers tell us it is. On the twice-annual student survey, Head students respond that their teachers hold them to high expectations and believe in them, and that they feel heard and included in their education and student experience. Teachers feel that school leadership is trustworthy, is positive, and helps them grow as educators. As important, Head’s academic data is impressive compared to other middle schools. Not only are students across the board performing at a rate in the top 25% of MNPS middle schools, but all students – in every ethnicity and sub-group measured for academic data – are performing in this top quartile when compared to their peers – one of only four out of roughly 50 middle schools in MNPS that has this level of equitable outcomes for all subgroups.

Math Student Achievement:

% On Track or Mastered

Source: TN Department of Education State Report Card, 2018–19 school year

English Language Arts Student Achievement: % On Track or Mastered

Source: TN Department of Education State Report Card, 2018–19 school year

Positioning teachers as experts

Dr. Williams’ expectations for her teachers are high, yet she provides a great deal of flexibility on how teachers go about reaching those expectations. She trusts that if a teacher is making a decision to teach in a certain way – even if it means each classroom might look a lot different – it is for the benefit of students. Since she and her leadership team are constantly checking in on teachers in their classrooms, she knows when expectations are and are not being met. Expectations and goals are clearly defined – 91% of Head’s teachers feel this way, compared to 65% of MNPS middle school teachers on average – and leadership demonstrates follow-through – 86% of Head’s teachers feel school leaders are knowledgeable about what is going on in classrooms, compared to 54% of MNPS middle school teachers on average.

This allows her to afford plenty of autonomy to teachers to lead their classrooms and instruct using innovative methods that work for them. Dr. Williams requires her teachers to open each lesson with a warm welcome and end with an optimistic closure – whether it be a special greeting, a game or activity to build community among students and teachers, or a class-curated playlist to guide work time or classroom procedures. She describes a key aspect of the culture she wants teachers to create for students as “bringing them into your calm.” She models this for her staff daily, bringing teachers and staff into a calm that starts at the top with school leadership.

Dr. Williams understands that teachers need to have the flexibility to meet her expectations in a way that is authentic for them as well as their students. “SEL is not a one-size-fits-all approach,” she said. “What works for fifth grade teachers probably won’t work for eighth grade teachers.” The flexibility that teachers are given to meet this and other expectations for instruction or classroom management leads to greater buy-in from teachers and more effective implementation of strategies that make a real difference for kids. Teachers feel that they are being valued for the professional expertise and experience they bring to Head, and appreciate that the school’s leadership is so intentional about making them enjoy working at the school. Some 88% of teachers at Head report that teacher satisfaction is important to school leadership – 32% above the district average for middle schools. In order to allow her teachers to fully teach students through an SEL lens, she leads her school and team in the same way.

If a teacher is struggling with instruction, classroom management, or the effective integration of SEL, she points them to other teachers who are doing well in that area, or helps facilitate a Professional Learning Community to promote teacher collaboration and peer observation. Rather than give that teacher a directive herself, she leverages an impressive slate of educators as the greatest in-house professional learning resource she can offer her team. And data shows she is right to do so – 93% of teachers say that their colleagues’ ideas are helpful for improving their teaching, which is 23% higher than district average for middle schools. And 69% of teachers feel that they are able to provide input when school leadership is making important decisions, a whopping 30% above district average for middle schools.

Operationalizing the vision

As do all principals, Dr. Williams has to make key decisions with her school’s funding that affect the work experience of teachers. She could allocate dollars to supplies or infrastructure if she were to reduce the number of staff positions by consolidating teacher responsibilities. However, since this would increase the different number of classes one individual teacher would have to teach – i.e., teaching both science and social studies, and thus having to plan lessons for, prepare materials for, and keep track of two entirely separate courses – Williams chooses not to. She opts to allocate funds in a way that keeps teachers teaching only one course, when possible, and teaching a course that they want to teach. This decision allows Head teachers more time to plan thoughtful lessons and eliminate stress, and reinforces Dr. Williams’ message that teachers are the drivers of change in her building. As one teacher explained, Dr. Williams is “thoughtfully logistical,” saying “I’ve never worked with someone with so much thoughtfulness about how decisions will impact teachers.”

Every Sunday, Dr. Williams sends out a weekly “Heads Up” email to teachers that previews the week’s schedule, priorities, special events, and other pertinent information. The purpose of this consistent, clear communication is to eliminate confusion for teachers and reduce the number of things they need to keep track of, so that they can put their full attention and time on teaching high-quality, engaging lessons. By sending this weekly email, Williams creates a structure for her teachers to plan out the week, think about what they want to accomplish given other responsibilities, and focus on teaching.

This is felt and appreciated by teachers at Head. Some 97% of teachers at Head Middle feel that their school leadership effectively communicates important information to them – 40% higher than the average for middle schools in MNPS, according to fall 2019 Panorama survey data. “Nothing will catch me off guard,” a teacher shared. “I can focus completely on teaching because I don’t have to think about what is going on that day or coming up next.” And 89% of staff feel that they are well-informed of school policies and procedures, 31% above district average for middle schools.

By addressing teacher needs holistically and building systems that allow them to have autonomy over their classrooms, Dr. Williams is cultivating a work environment in which teachers want to teach: one that is driven by a focus on the social-emotional learning and care not just for students, but for adults as well. “I work hard to meet Dr. Williams’ expectations,” one teacher said, “because I know she is meeting mine.”

By addressing teacher needs holistically and building systems that allow them to have autonomy over their classrooms, Dr. Williams is cultivating a work environment in which teachers want to teach: one that is driven by a focus on the social-emotional learning and care not just for students, but for adults as well.

Continuing to climb

While Head is demonstrating above-average academic achievement, the school still has opportunity to grow students even more as they climb further to thriving. Currently, about 60% of students are achieving at the academic threshold that earns them automatic enrollment at Martin Luther King Jr. school – the seventh to 12th grade academic magnet that Head feeds into – after sixth grade, the first exit point for students going from Head to MLK. The second exit point, after eighth grade, currently sees fewer students achieving the academic achievement necessary to automatically enroll in MLK, only 40%. Dr. Williams’ goal is to make these numbers match – to bridge the gap between the “early” group of students qualifying for admission into MLK and those who finish out middle school at Head. The school culture that has been cultivated and nourished through the intentional integration of social, emotional, and academic expectations is a strong indicator that the school will grow toward this goal.

Dr. Williams is dedicated to making Head a place where teachers want to work and where students want to be. Strong academic expectations infused with SEL practices that don’t stand alone, but are what make learning possible, engaging, and long-lasting for both students and adults allow her to make this vision a reality. By creating a school culture that clears the path for SEL practices and expectations to be “a blessing and not a burden” for teachers, they will implement them more readily and effectively. And when this happens, students benefit immensely. “While school is a place for academics, it should also be a refuge for students,” Dr. Williams said. “I firmly believe that.”